Coveo’s Query Suggest model provides highly relevant and personalized suggestions as users type. In this blog post, I will explain how Query Suggest works in the back end, and how it uses mutli-threading to provide results at high speed.

Introduction

Query Suggest is a feature provided by Coveo ML that suggests completions to search queries while users are typing. Query Suggest is remarkable among the stable of machine learning models developed by Coveo in that it has to be very fast; to deliver an acceptable user experience, suggestions have to be computed in just a few milliseconds. Consequently, when Query Suggest is not very fast, we have a problem on our hands.

In early 2021 while developing new features, intermittent spikes of unsatisfactory performance emerged in our query suggest test servers, prompting us to reexamine the model’s performance in detail. In particular, we focused on evaluating the multi-threaded components.

In this blog post, I’ll do a deep dive into how Query Suggest comes up with suggestions and describe our multi-threaded performance problem and its solution. The first three sections of this post are written to be accessible to non programmers, after which a more technical discussion begins. Let’s dive in!

Query Suggest

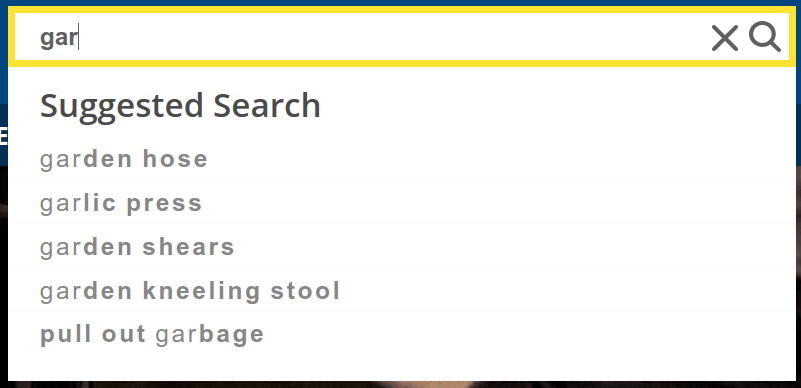

The Query Suggest feature provides a user experience that is similar to the one provided by many other search services: as the user types, a list of suggestions appears for ways to complete the query. As the user continues to type, the suggestions become more refined and particular. This kind of functionality is useful both for saving the user’s time and also for helping them to discover content related to their query. For example, a user searching for “garden tools” will instantly discover that the site also offers “garden shears” and “garden hose” as they begin to type.

A query suggestion model can make use of multiple sources of information to quickly narrow down the many possible suggestions in order to provide relevant suggestions as early as possible. Coveo’s Query Suggest model uses three main sources of information to rank suggestions: text similarity, historical data, and user features. To explain how each of these works, I’ll give an example of how we could construct a query suggest model by iteratively adding these sources of information.

Let’s start with a model that uses only text similarity. This model could simply suggest completions to the query being typed which 1) are valid words in the main language of the site and 2) have as a prefix the letters the user has already typed (here, “is the query a prefix of the suggestion” is a very simple type of text similarity algorithm). For example, if the user has typed “gar”, we can suggest “garden”, “garlic”, “garage”, etc. This type of model would be very fast, and almost useless! What good is this model that keeps suggesting “gargle” whenever a user performs a search in your garden supply store?

The model could be improved substantially by taking into account the second source of information: historical data from previous searches on the site. For example, we could use the list of queries users have previously searched for as a source of suggestions. This would restrict the domain of suggestions to the kinds of topics users of the site have already expressed interest in. No more suggesting “gargle”. We could then calculate which queries have historically led to clicks (rather than follow-up queries), indicating that the query is a particularly relevant one, and prefer to suggest it. Next we could – well, I’ll stop here, I can’t give all the secrets away! Suffice to say that Coveo’s Query Suggest model uses multiple kinds of historical data, content data, and text similarity algorithms in order to compute and rank suggestions.

Finally, we can take into account the third source of information: user features. This means considering which user is currently typing, and tailoring our suggestions for that particular user. For example, if we knew the user had recently looked at laptops on the site, we could decide to suggest queries to them which are more likely to include laptops in the results. This helps users to find the results they’re looking for even faster. There are many ways to take the user’s features into account in order to provide a personalized experience. Much of our work in the last six months on the Query Suggest model has involved integrating new types of user features into our personalized suggestion ranking process.

By combining these and other sources of information, Coveo’s Query Suggest can provide highly relevant and personalized results. However, the more information we take into account for each suggestion, the more difficult it is to provide suggestions in a very limited time frame. We make extensive use of parallel processing via multi-threading to make this possible.

What kind of work does Query Suggest do?

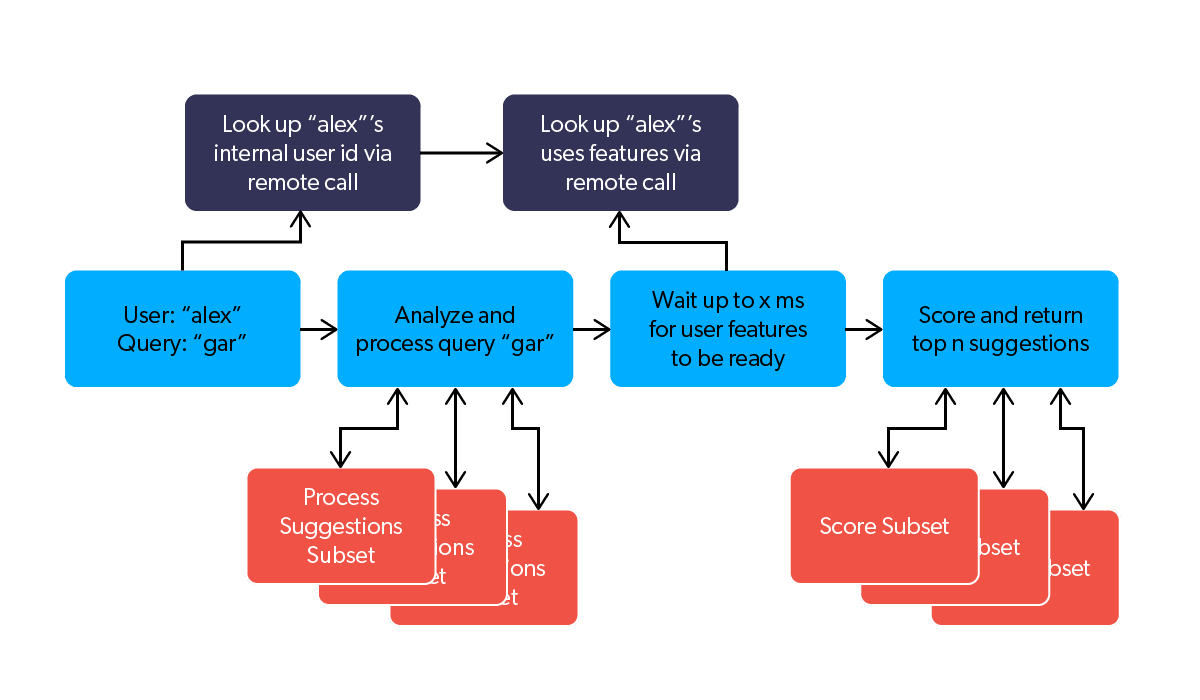

In this section, we’ll go into detail about how our Query Suggest system processes a request for a suggestion. Remember, we have a very limited time budget (10s of milliseconds) to produce suggestions. Inside this budget we need to perform three expensive operations.

The first is to look up the user’s internal id (see User Stitching) and associated features. This data is stored in remote databases, so the operation is expensive because we need to wait several milliseconds for the data to be looked up and returned over a network.

The second is to determine the set of suggestions that are appropriate given the language used and filters applied to the query. This operation is expensive because there are potentially millions of suggestions to filter and sort through.

Third, the filtered suggestions need to be scored and ranked given the query and the user’s particular features, so that the most relevant suggestions appear at the top of the list. This is an expensive operation, as our scoring function is a complex computation that combines many different sources of information.

Each of these expensive operations uses multi-threading to speed it up, illustrated above. Multi-threading is a way of allowing a program to do multiple things at once in parallel. Each of the tasks a program is currently working on is handled by a thread. For example, the calls to remote databases to look up user features are started immediately and waited for by a thread (green in the illustration above). Both the processing and ranking of suggestions are processed in parallel using map-reduce style processing; the list of possible suggestions is split up into chunks, each chunk is assigned to a thread which processes just that chunk, then the results of each thread’s work is combined (red, orange, and yellow in the illustration above). Combined with caching the results of these expensive operations where possible, this procedure is very efficient, and typically computes and returns suggestions in less than 10 milliseconds.

Scala’s multi-threading tools

Query Suggest is implemented in Scala, which provides a nice set of built in tools for doing multi-threaded programming. For example, if you have a slow request to a database to perform and you don’t want to block the program from continuing while this occurs in the background, you can simply use the Future class to assign that call to a separate thread and continue your program’s work until the result is needed. In Query Suggest, we use this tool to fetch the user’s internal id and features while the main thread continues to process the query.

// Listing1.scala

import scala.concurrent.{Future, blocking}

import ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

// assign the work to some other thread and immediately continue

val dbResultFuture = Future { blocking { remoteDatabaseCall() } }

// register a callback to print the value returned from the database at some point in the future.

dbResultFuture.map(result => println(s"The database returned $result")) Alternatively, if you have a large collection of data that needs to be processed as fast as possible making use of many CPU cores you can use the parallel collection tools to easily implement a map-reduce style parallelism (that is, splitting the work into chunks, processing each chunk in parallel, then combining the processed chunks). We use this feature to process and rank collections of suggestions. This feature is even easier to use: simply invoking the par() method on a standard collection will return a parallelized view of that collection, where any map, filter, or fold will be accomplished by partitioning the collection into chunks and assigning the work to a collection of threads.

<code data-enlighter-language="generic" class="EnlighterJSRAW">// Listing2.scala import scala.collection.parallel.immutable.ParVector val myData: Vector[Int] = (0 to 10000).toVector val myParData : ParVector[Int] = myData.par myParData.map(x => x * 2) // accomplished via map-reduce style parallelism</code>

These are very nice abstractions – you can write parallel code without considering locks, pools, thread status, etc. But you can also get yourself in trouble. Like all abstractions, details of the underlying implementation can leak out, causing the facade of simplicity to crumble. This is exactly what we found to happen while experimenting with new Query Suggest features.

What can go wrong, and how to fix it

In the preceding section, you may have found yourself thinking: “this is very nice, but when we’re sending this work out to threads, which threads are we sending them to?”. This is a natural worry for programmers. In less abstracted interfaces, we typically have to concern ourselves with managing the creation and deletion of threads, or managing a limited pool of threads and a queue of tasks. Threads (and the CPU cores to execute them) are a limited resource, after all.

So, what actually happens when you schedule a Future (Listing 1)? There’s a hint in the listing: on the second line we import ExecutionContext.Implicits.global. The global execution context is essentially a dynamically growing and shrinking global static thread pool with a maximum of 256 threads (that is, it’s shared by the entire program, and can be executing up to 256 tasks at a time). This import statement adds this global thread pool as an implicit argument in the namespace. Thus, any Future we declare (without targeting another execution context explicitly) will be scheduled on this thread pool.

What about the parallel collections (Listing 2)? To make a short story even shorter: it uses the same global static threadpool. Here we have no hint. It’s simply an implementation detail of the parallel collections.

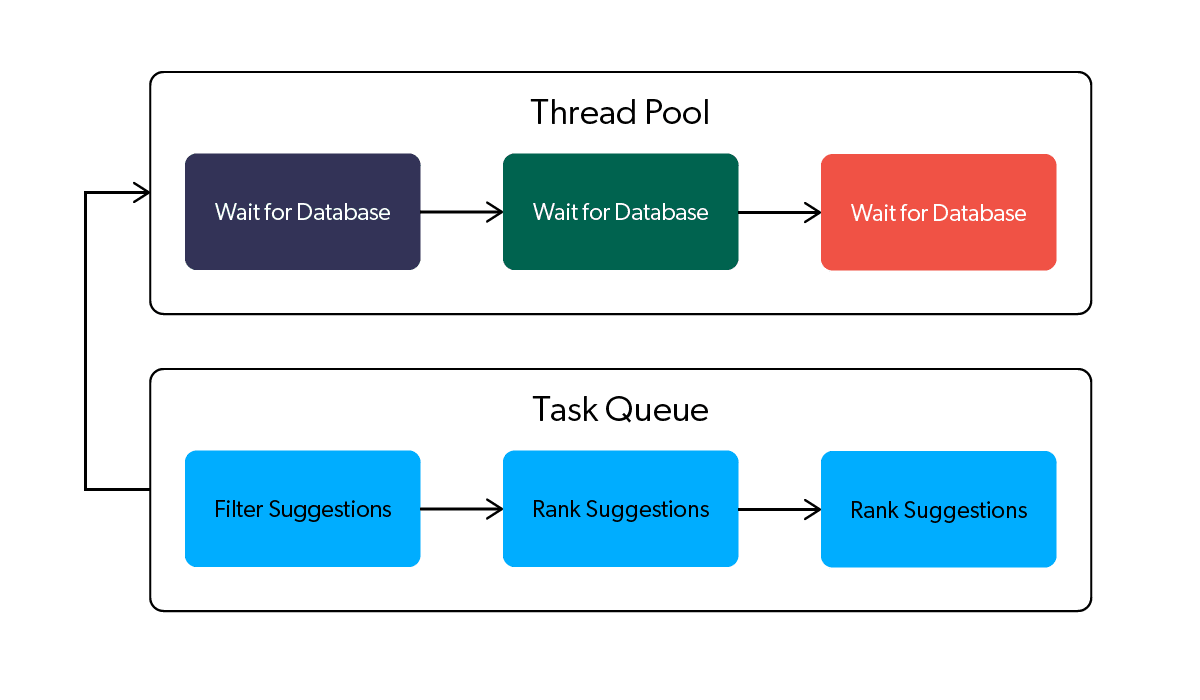

What this means for Query Suggest is that making use of both of these features can cause “waiting” tasks (i.e., IO bound) and “working” tasks (i.e., CPU bound) to compete for threads on the same small pool of threads! This is a classic anti-pattern in multi threaded programming.

Why? “Waiting” tasks (like requesting information from a remote database) don’t really have any interesting computations for the CPU to do; they consist of the program waiting for networks or file systems to shuttle data around. On the other hand, “working” tasks (like computing the relevance score of each suggestion given the user’s query and features) have lots of computations to do to keep the CPU busy. But when tasks are executing on a pool that has a limited number of threads, it’s possible that due to bad luck, all (or most) available threads start doing “waiting” tasks, even though there are “working” tasks that need to be done. The result is that while there is work the CPU needs to do, it can’t do it because all available threads are busy doing “waiting” tasks. This is a very undesirable scenario: the user is waiting for an answer, the computations required to answer the user are waiting for a chance to execute on the CPU, but all the threads that can execute on the CPU are busy doing nothing. The figure below illustrates the situation.

If this is a “classic anti-pattern” of multi-threaded parallel programming, why is it one we nearly fell into? It’s an easy mistake to make! Because the single global static thread pool that executes the tasks of Futures and ParallelCollections is referenced implicitly by both features, there is no direct connection between our “waiting” and “working” tasks visible in the source code. Instead, the connection between these bits of logic is buried in the implementation details of the libraries we were relying on. This kind of issue is happening entirely “under the surface”, and requires an understanding of both libraries to spot. As I mentioned earlier, it’s an example of a leaky abstraction: most of the complicated details of multi-threaded programming have been abstracted away by the Scala multi-threading tools, but at critical points the abstraction leaks and the complexities of the underlying system can not be ignored.

Once the problem is clearly identified, the fix is easy. All you need to do is create a separate explicit thread pool and assign all “waiting” tasks to this separate pool. This way, no “waiting” tasks can be prioritized over a “working” task, ensuring that the CPU is always used as soon as it’s available. An example is presented in Listing 3. This listing shows how a doWaitingWork function can be defined which assigns tasks to run on a cached thread pool, which is both distinct from the global execution context thread pool and does not have a limit on the number of threads it can create.

<code data-enlighter-language="scala" class="EnlighterJSRAW">// Listing3.scala

import java.util.concurrent.Executors

import scala.concurrent.{ExecutionContext, Future}

// An ExecutionContext backed by a CachedThreadPool used only for "waiting" work.

val exc = ExecutionContext.fromExecutor(Executors.newCachedThreadPool())

// Schedule the function to run on the separate ExecutionContext.

// No work scheduled using this function will interfere with ParallelCollection work.

def doWaitingWork[T](fn: () => T): Future[T] = {

Future{ fn() }(exc)

}</code> Implementing this kind of logic had a significant impact on the performance of our test engine under very heavy load, decreasing the average response time by a factor of 5 when the model is saturated with requests. Essentially this means we can expect much better and more reliable performance when the model is receiving many requests for personalized results.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we saw how Coveo’s Query Suggest integrates data from multiple different sources to increase relevance, how parallel processing is used to minimize latency, and how we should be wary of the hidden sharp edges of our tools when performance is critical.

We’re actively working on adding even more relevant and personalized results to Query Suggest. Each new feature we add puts more pressure on the performance of the model, creating a delicate balance that is a satisfying challenge to maintain.